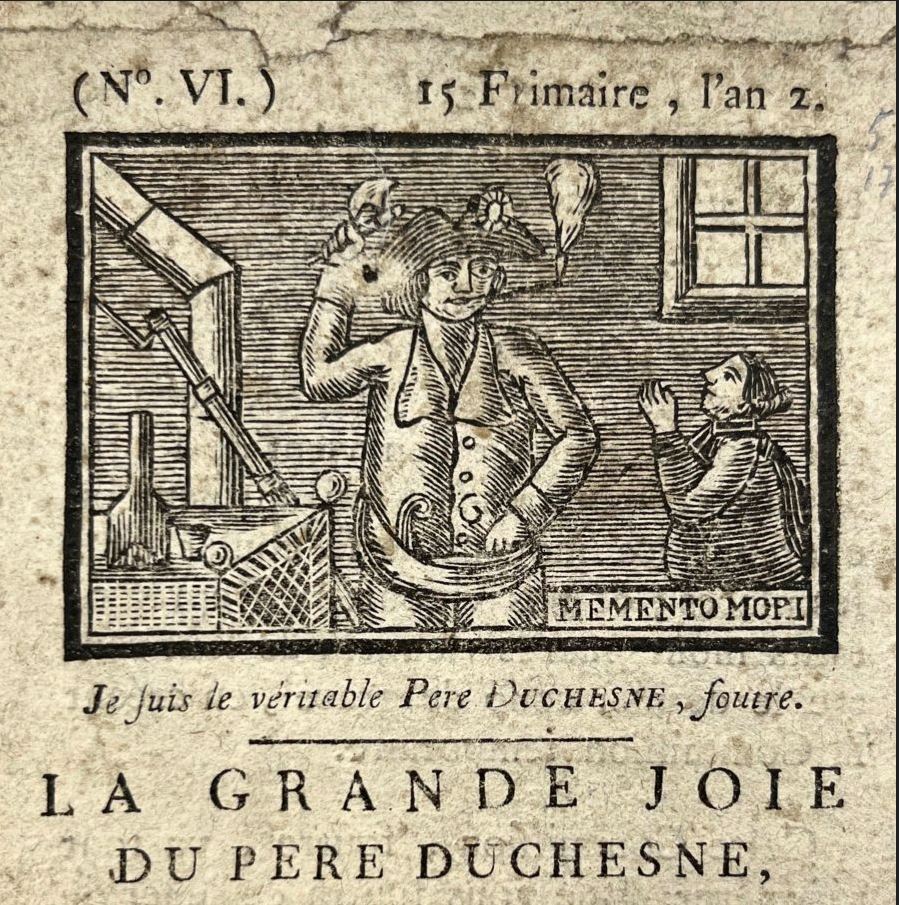

Le Père Duchesne, or Father Duchesne, is a straightforward and cocky character invented by the French satirists of the 18th century. In 1790, René-Jacques Hébert entitled his revolutionary journal after him, and he added an engraving to each issue that represented Father Duchesne as a fat moustachioed man with a crazy eye, about to chop a priest with an axe. The words memento mori were written beside him, as a warning. And the caption reads: “I’m the true Father Duchesne, for fuck’s sake!” Don’t you trust this naive and clownish representation—Father Duchesne was a serious man, and his words meant blood and death.

Several journals entitled Father Duchesne were published at the same time: one by Lemaire and Jumel, and another one by Robin and Colombe. But with 385 issues published between 1790 and 1794, Jacques-René Hébert became the voice of Father Duchesne. To make sure you’re holding a “true Father Duchesne, for fuck’s sake”, check the printer’s address. The BnF website dedicates a page to Hébert*: “The address of the printer, whether real, fake or ironic, varies: Printed at Father Duchesne’s, (...) at Tremblay, (...); from the print shop Street Equality, courtyard of miracles (...).” Jumel and Lemaire’s journal was printed “Rue du Vieux-Colombier”, while Robin and Colombe’s was located “Rue Henri IV”. The competition was fierce and ruthless among them. The BnF website again: “The (...) vignette (described above) was first used in December 1790 by Jumel. Hébert featured it up from issue #13 onward.” The priest featured on the engraving is Abbé Maury—a fierce opponent to the Révolution, and Hébert’s favourite enemy. “The words ‘memento mori’ are directly addressed to him,” the BnF website states. “But the clergyman went on exile, and escaped the guillotine”—unlike Hébert.

Hébert was nobody before the Révolution, a former stove seller, he claimed—hence the overturned stoves printed at the bottom of his journal from issue #23 onward. A man who “sprung from the mud,” Mercier says (Le Nouveau Paris, 1799). Hébert deliberately used violence to make his point, including the use of bad words such as foutre (fuck), and various slang expressions that the French are still using today such as “daron” and “daronne” to refer to the King and Queen (nowadays it means “father” and “mother”), “foutre le camp” (to run away), or “n’y voir que du feu” (not noticing). When he went on trial in 1794, Hébert explained that he “intended to talk to the ignorant, who couldn’t understand certain things weren’t they told in their own words.” According to another historical figure, Desgenettes, this language “wasn’t Hébert, who was on the contrary very polite.” He was also advocating physical violence against the enemies of the Révolution. To such an extent that he became Marat’s spiritual heir after the latter was murdered (www.rarebookhub.com/articles/3425). He was a member of the Commune when the Terror started—and his the words of Father Duchesne directly or indirectly sent many to the guillotine.

That was quite a social climbing for Hébert, but he went too far, for fuck’s sake! First when he accused Queen Marie-Antoinette of having an incestuous relationship with her young son during her trial. This was but a complacent and dirty political lie—everyone knew it, and many despised him for it, including among Marie-Antoinette’s enemies. But his worst mistake was to irritate the dreadful Robespierre, who took action in 1794. Hébert was arrested for plotting against the Révolution. This was a false accusation, but Hébert knew how it went. He was tried, and condemned to death, six months after mocking the Queen’s last moments in his journal. Memento mori, Father Duchesne.

Unlike Marie-Antoinette, Hébert didn’t behave with dignity on that dreadful day. Lenôtre reports (La Guillotine pendant la révolution—Paris, 1893): “On October 16, it was Hébert’s turn to “play the hot handle” (to be guillotined). He behaved so cowardly on that occasion that the 17 prisoners who were to die with him were disgusted. As soon as he came out of the Palais (of Justice), he was livid; he was dressed with taste, as usual, but his clothes were in disarray. He was in a flood of tears, and sweat was running down his forehead. The population stood on the way of the cart, insulting and booing him: “Hey, Father Duchesne! You’ll catch a glance at the skylight, and you’ll tell us tomorrow, in your journal, what we see from there!” They had to pull him down the cart, and to sit him down on the ground, as his legs couldn’t support him. He was almost already dead with fear when they tied his unconscious body to the plank of the guillotine.”

A few days later, GF Galletti, Printer of the Journal of the Laws of the Republic, published a relation of Hébert’s execution. The title says it all: Father Duchesne Mad with Rage to see his head fall through the national window...** In this satirical brochure, Pluto welcomes Hébert: “Here you are, one of us now, my dear Hébert. And you come just like all my aristocrat friends, ball in hand. The devil knows, I wasn’t expecting you so soon, nor so short.” A cynical world, indeed—but worthy of Father Duchesne!

Duchesne didn’t die with Hébert. He was kept alive for a while through publications such as Mother Duchesne, or Father Duchesne’s Son. Then he resurrected during the 1848 revolution, and during the Commune, in 1871. Yet, notwithstanding his predecessors or successors, it seems like Hébert will forever remain “the true Father Duchesne.” We’ll leave his epitaph to Lenôtre: “Many revolutionaries have been rehabilitated since, but I don’t think someone will ever have the power to clear Hébert’s ugly name—he’ll forever be displayed at the pillory of history.” Hell yes—for fuck’s sake!

Thibault Ehrengardt